Madras Curry Blend

JEWEL IN THE CROWN - an excerpt from the cookbook On The Curry Trail

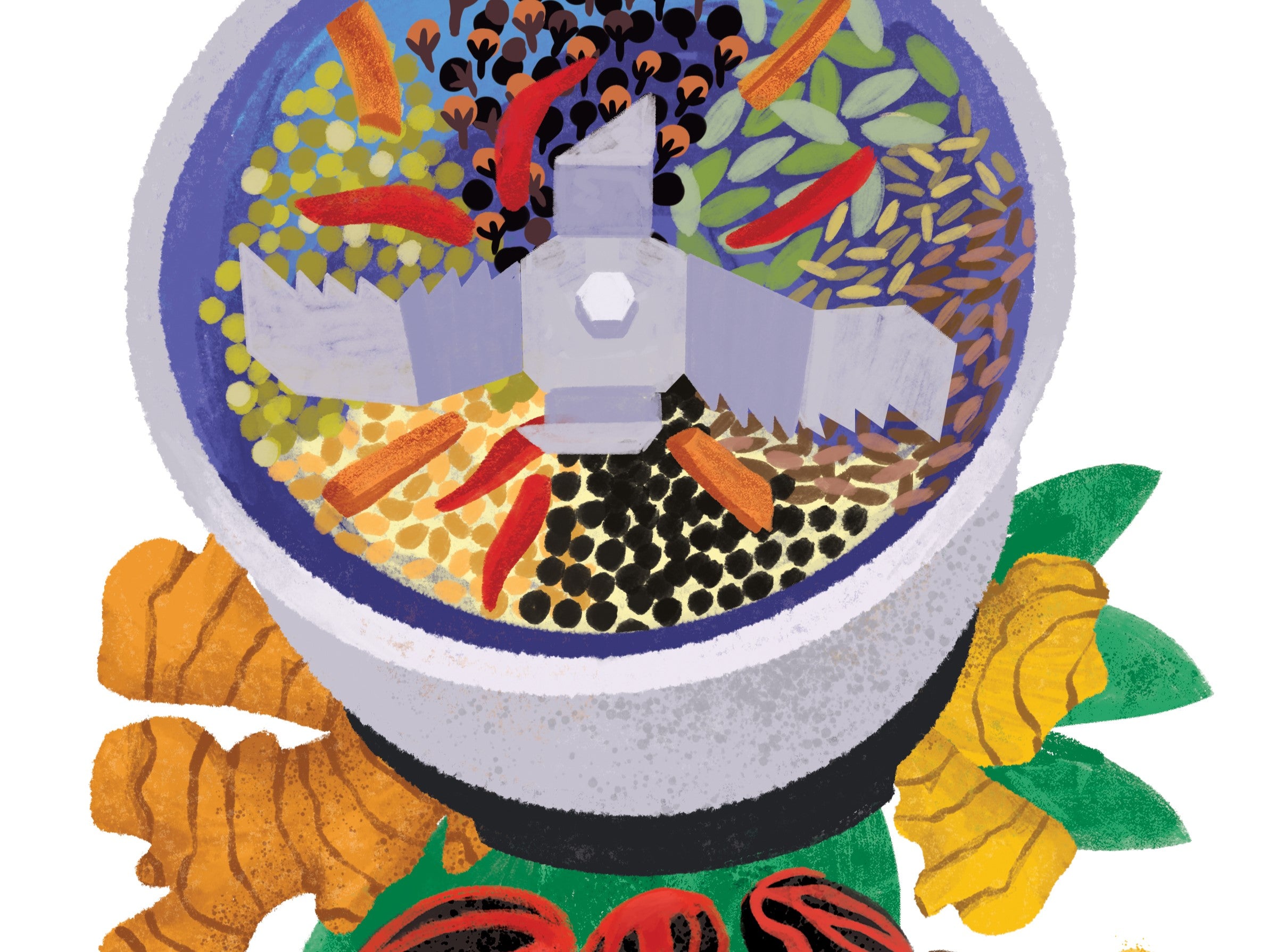

Madras curry powder is a perfect example of Britain’s colonialist tendency to simplify and package all that was foreign, complex, and “exotic.” India, their “jewel in the crown” (which they inhabited, first as traders and then as rulers, from 1608 to 1947), enticed Britain with its aromatic, peppery, complexly layered, 6,000-year-old dishes: There is evidence of mortars and pestles having been used in the 4000 BCE Mohenjo-Daro civilization of the Indus Valley! Indian cooks had a seemingly chaotic way of spicing food—oftentimes roasting, toasting, and pounding a combination of disparate ingredients—but it resulted in flavors that were harmonious, layered, and nuanced.

In Oxford Companion to Food, Alan Davidson takes us back to 1885 when Colonel A. R. Kenney-Herbert, a distinguished writer on the foods of the Anglo-Indians, took a stab at a “stock for curry powder.” It incorporated turmeric, coriander seed, cumin seed, fenugreek, mustard seed, dried chilies, black peppercorns, poppy seed, and dry ginger—and he offered up the recipe even though commercial curry powder mixtures were being used in Britain at the time.

For epochs prior, South Indian cooks were sun-drying these same spices to flavor signature stews called sambars. A unique combination was fashioned in each home kitchen, defying a homogeneity throughout all South Indian kitchens. However, the British creation of a uniform and good-tasting Anglo-Indian curry gained a foothold and opened the world to Madras curry powder, a simplified adaptation named after South India’s coastal city of Madras (now called Chennai).

Yes, you can procure many kinds of Madras curry powders all across the globe in the spice aisle of any supermarket, but making your own is simple, time efficient (you really can’t spare five minutes of your time to make this?), and frugal. Here is my version, used in many of the recipes in this book.

Excerpted from On the Curry Trail: Chasing the Flavor That Seduced the World by Raghavan Iyer. Illustration by Neethi (@Kneethee). Workman Publishing © 2023.

✦ Ingredients

- 2 tablespoons coriander seeds (see Tips)

- 1 tablespoon cumin seeds (see Tips)

- 2 teaspoons fenugreek seeds

- 1 teaspoon fennel seeds

- 1 teaspoon black or yellow mustard seeds

- 1 teaspoon black peppercorns

- ½ teaspoon whole cloves

- 1 teaspoon cardamom seeds (see Tips)

- 8 to 10 dried red chiles (like chile de arbol) stems discarded

- 2 sticks cinnamon, broken up into smaller pieces

- 1 tablespoon ground turmeric

- 1 teaspoon ground ginger

- ½ teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

✦ Instructions

- Pile all the ingredients except the turmeric, ginger, and nutmeg in a spice grinder (or a clean coffee grinder). You may have to grind the whole spices in batches if your grinder is unable to accommodate that voluminous pile in one swoop. Grind the ingredients to the consistency of finely ground black pepper, tapping the lid to release any of the intoxicating blend back into the grinder’s cavity. Transfer to a medium bowl. Repeat with the remaining whole spices.

- Stir in the turmeric, ginger, and nutmeg to fashion a blend that may very well draw the word “wowee” from your lips (after the nose does the talking).

- Store this spice blend in an airtight jar (preferably glass) in your cool, dry pantry, away from sunlight. In my opinion, refrigerating the blend will adversely affect its flavors (because of the moisture in the cooling unit). This blend will keep for up to 6 months.

Tips Part of the Apiaceae—also called Umbelliferae—family (think parsley, fennel, and carrot), the coriander plant, indigenous to the Mediterranean region, is known by many names: cilantro, Chinese parsley, and Arab parsley. The leaves and seeds have found extensive usage in food, medicine, and preservation. The Egyptians were using it as early as 1352 BCE and the Buddhist emperor Ashoka introduced it to India around 200 BCE. The lightweight and light-colored brownish-yellow seeds are highly aromatic, very citrus-like, especially when ground fresh. Coriander is a key ingredient in curry powders; I highly recommend buying it only as seeds. (You’ll find a lengthier description of eight different flavors of coriander in my 2008 book, 660 Curries.). A crucial spice along the spice route, cumin is also a member of the Apiaceae family and is the Mediterranean’s gift to the world. Many curry powders and other blends (like Morocco’s ras al hanout, used in Slow-Cooked Chickpeas with Saffron on page 106) incorporate this slender, spindle-shaped spice that is musky, nutty, earthy, and highly aromatic. True cardamom, indigenous to the hilly areas of southwestern India in Kerala, is the second most expensive spice in the world (next to saffron), and its heady menthol-like aromas have won the world over in savory and sweet recipes. A close cousin to ginger and turmeric, these plump green pods (reminding me of bleeding hearts) are hand-picked and sun-dried or spread out on drying racks in small sheds. They are available at Indian markets, some supermarkets, and online; some stores stock the bleached-white version of green pods, and I have found no difference in taste and aroma between them. To get at the seeds, pry open the pod with your fingers. A whack with the broadside of a knife also helps loosen the pod. Remove the black seeds from within and discard the skin and small vein that holds them together. Pods vary in size but 6 to 8 should yield ½ teaspoon of seeds; you’ll need 10 to 12 for a whole teaspoonful.